Romans

In the grounds of Littlecote House you will find the largest and most complete Roman villa complex on display in Britain (and Warners' best-kept secret!). The stunning Orpheus mosaic never fails to astound and impress and it is just a short walk from the old house.

Discovered accidently by the Littlecote steward in 1727, it caused a sensation at the time and was declared by the Antiquarian Roger Gale to be “the finest pavement that the sun ever shone upon in England”. The mosaic was re-buried and subsequently considered broken up and lost. But in 1976 it was rediscovered by two local archaeologists, Bryn Walters and Bernard Phillips, and the whole site painstakingly restored over a 13-year period.

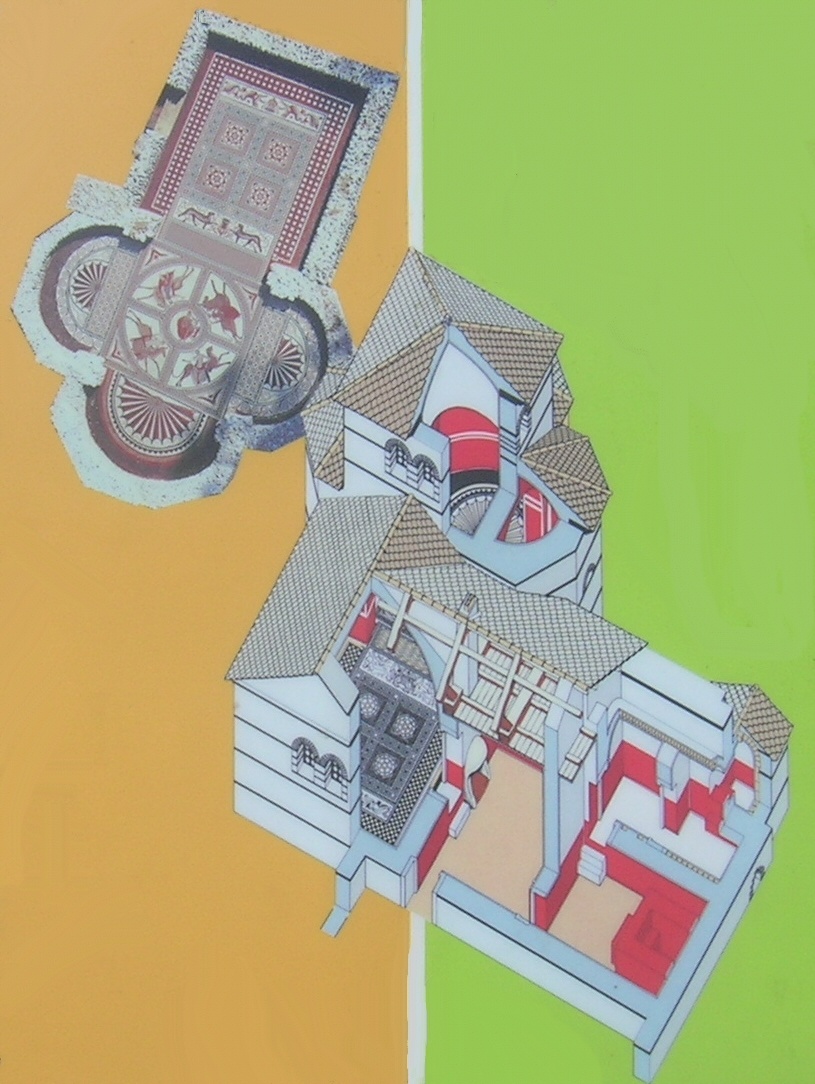

At the villa site are several detailed information boards with illustrations of the villa, created and installed by Bryn and illustrator Luigi Thompson, from which these extracts have been taken. Don’t miss it!

The Villa Complex

Between the first and eighteenth centuries, seven main periods of structural development took place by the side of the River Kennet. These ranged from a native British round-house of AD 60, through a series of domestic work buildings, to the unusual and exotic ‘Orphic’ structure of AD 360.

During the medieval period, the last Roman structures were gradually demolished and used as a source of building material. Between 1650 and 1780, above the remains of the east end of the ‘Orphic’ building, a brick-built cottage was developed into a well-appointed house, probably the hunting lodge for Littlecote Park. It was in the garden of this house, whilst digging post holes for a fence, that the Littlecote steward found the mosaic in 1727.

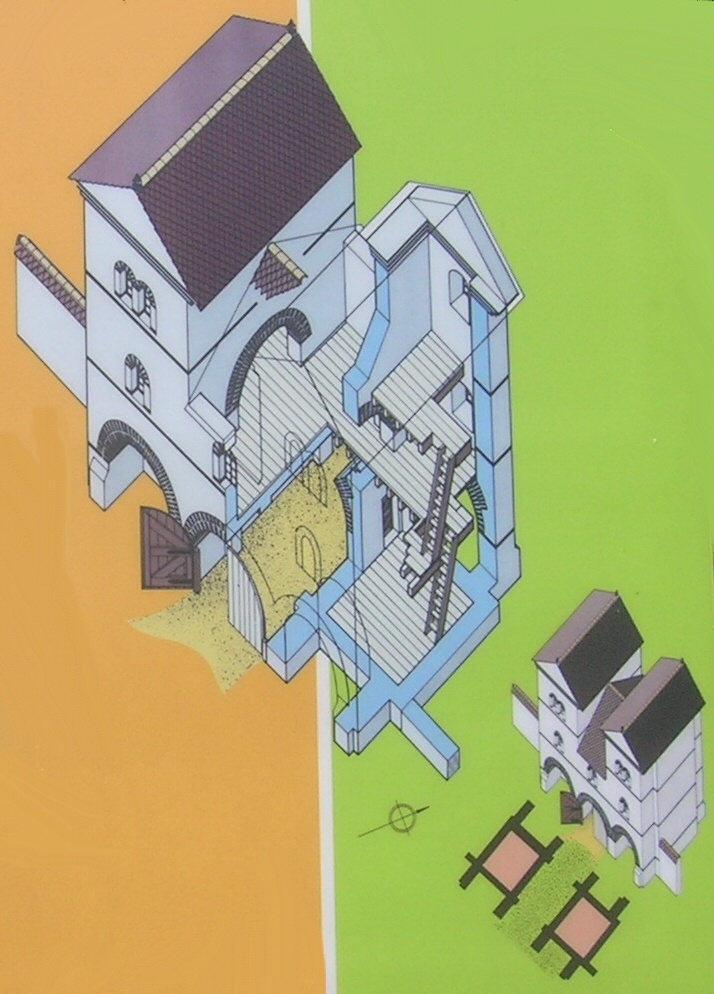

The Gate House

This once lofty building formed the main entrance to the villa and is the most important Gate House yet found on any villa in Britain. Triple arches supported two towers flanking a tunnel-like entrance passage.

The two small rooms on the grounds floor could have accommodated the gate keeper’s lodge and possible storage areas. It is the massive buttress foundations, projecting from the front and rear corners of these rooms, which provide the structural evidence for the reconstruction.

The arched vaults would have supported a large cross hall on the first floor, extending out beyond the ground floor rooms. This building could have functioned as a grain store with hatches in the floor leading through the top of the external arches for hoists to lift and lower sacks to carts below.

The Orphic Building

The last of a series of agricultural buildings was spectacularly transformed around AD 360. Most of the building was demolished and only its west, north and east walls were retained. They then formed part of an unusual building which has been interpreted as a telesterion, a sacred precinct dedicated to the cults of Orpheus and Bacchus.

A decorated entrance hall, or narthex, was added onto the original east wall, looking directly down the curve of the river. From this a double door led into an enclosed and paved private courtyard. At the far end a small door gave access into an ante-chamber with a bath-suite to the right and steps on the left led into an exotic triple-apsed hall, a triconch, unique in Britain. This was paved with a most elaborate and evocative mosaic.

Although usually referred to as the Littlecote Orpheus mosaic, the predominant theme throughout the floor is an allusion to the late Roman philosophic interpretation of the cults of Bacchus, who promised everlasting life to his followers. The main figured area of the mosaic depicts, at its centre, a traditional image of Orpheus, the musician and priest to Apollo, the sun god. In the surrounding quadrants, four goddesses, representing the four seasons, dance a pirouette in front of fast-running beasts.

Rediscovery and Restoration

Once re-buried, the mosaic’s location was forgotten, but it was nevertheless well documented. The Littlecote steward William George, who first discovered the mosaic in 1727, made coloured drawings of it, and it was from these that his widow completed an intricate piece of needlework in his memory. The needlework was mounted and hung in the old house until 1985 when it was sold by the then owner, Peter De Savary. Embroidered panels within the work described its discovery and iconography.

William George reported his find to the Earl of Hertford, then President of the Society of Antiquaries, and it was Hertford who commissioned the engraving of 1730 by George Vertue, the court artist, from remarkably detailed drawings by Samuel Lysons. These two pieces of “evidence” provided both the means of rediscovery and of its restoration.

The work was sponsored initially by Sir Seton Wills, who had inherited the estates from his father and grandfather, tobacco manufacturers. When entrepreneur De Savary bought Littlecote from the Wills family in 1985, he continued with the funding. The excavation and restoration of the Roman villa complex, of which the Orphic building and the mosaic are part, took a total of thirteen years to complete. The site is still part of the Littlecote estate and thus owned by Warner Leisure, who are responsible for its maintenance.

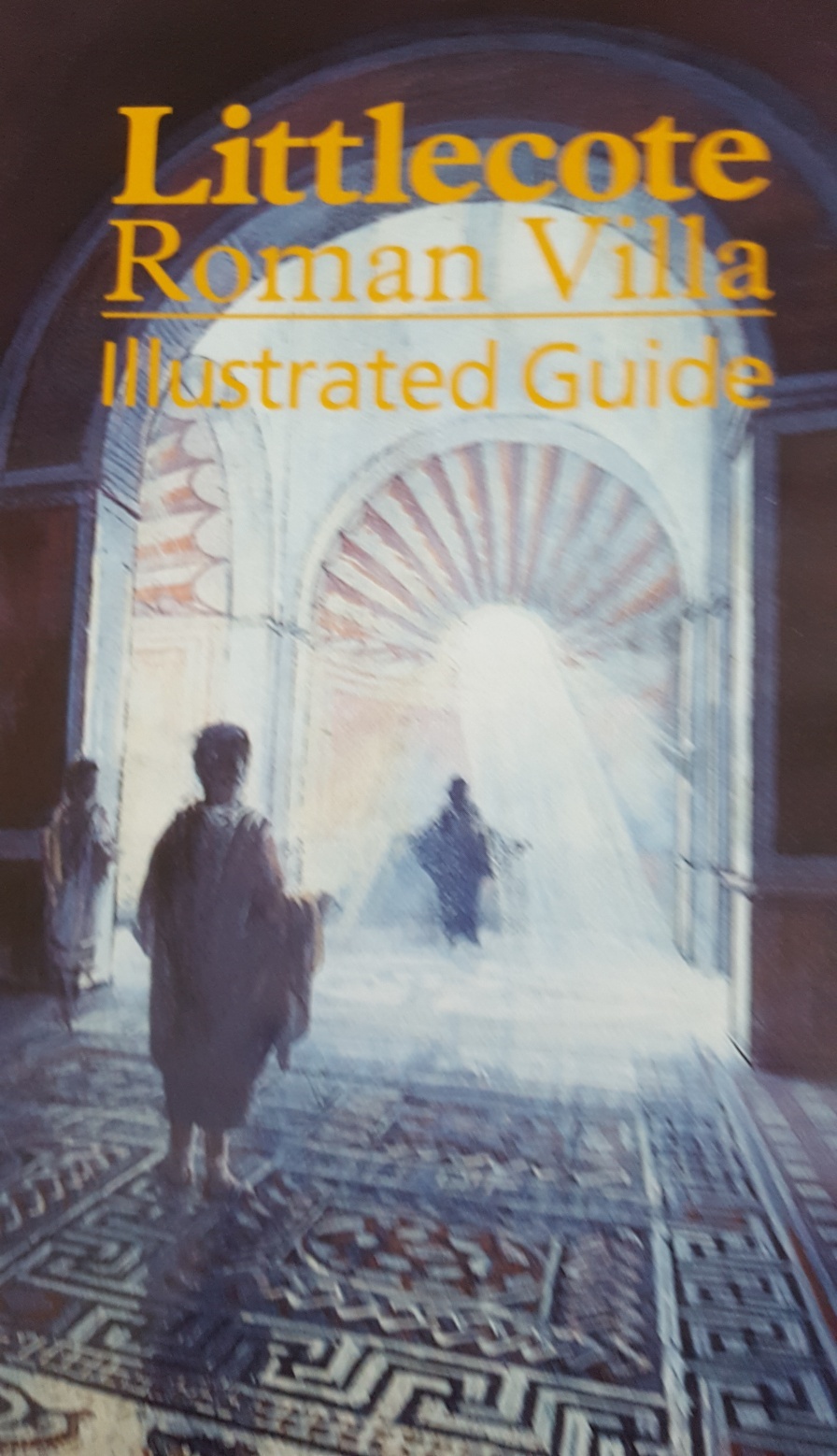

The original illustrated guidebook has an artist's impression of the interior of the Orphic building on its cover.

It is available in the Littlecote gift shop at £3.

warnerleisurehotels.co.uk/hotels/littlecote-house-hotel

warnerleisurehotels.co.uk/hotels/littlecote-house-hotel